It’s unusual to have a father who’s a Talmudist, a philosopher, a master of tradition and transmission. I’m lucky enough to have him as both father and teacher, because my father is my teacher. As a child, I’d watch him prepare his lessons and lectures, and I’d browse through the forest of books that was his office. He traveled a lot because he taught in Brussels, Switzerland and then in Bordeaux, where he was based at the university. He was between two cities, two countries, two suitcases.

He has a mission that transcends all else, that of transmitting. He devotes his life to teaching Judaism.

As a teenager, I was fascinated by Jewish thought, and that’s how he taught me everything. With him, I also met the great thinkers and commentators, from Rachi to Levinas. He opened up a world to me. He opened up the world to me. My father has no equal when it comes to explaining philosophy, bringing it alive and up to date. He’s a great teacher. I followed in his footsteps, studied philosophy and became a philosophy teacher. Then I started writing novels, which is not an attempt to escape my father’s sphere, but rather to radiate his aura. In all my books, there’s my father, as a character, in dialogue, on every page. For me, writing is linked to the father. So why not write about my father?

But also, how can I write about my father, when he is such a mystery?

Such a work is possible, provided that we conduct a major investigation and interview those who knew him, his family, his many students, and visit his places, from Morocco to Canada, because my father talks a lot, but not about himself.

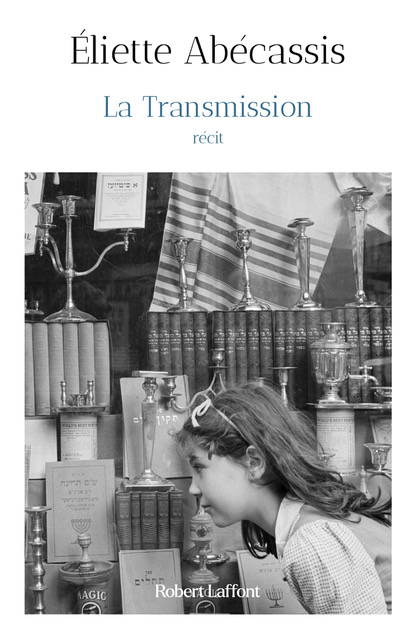

Armand Abécassis is at a crossroads. Born in Morocco, living in Strasbourg, professor at the University of Bordeaux, he combines Eastern culture with the cult of the West, the openness and intellectual hospitality of the Mediterranean with French rigor and rationalism. But it’s the traditional Jewish transmission under which he grew up that has shaped his personality since childhood, from the Heder and the Moroccan rabbis who left an indelible mark on him. The various educational environments that imbued him with this, from the Alliance to Orsay, will be evoked in this book, as they were for him a veritable cultural bath in which he learned to think and behave. He discovered the difference between informing and training, instructing and educating. Through his journey, a whole section of Judaism is brought to light, from the rue des synagogues in Casablanca to the Alliance israélite universelle in Paris, where he teaches, via the large Jewish community in Strasbourg, where he served for thirty years.

Like Ivan Jablonka’s masterpiece Histoire des grands-parents que je n’ai pas eu, which resurrects the Ashkenazi world, I would like to resurrect the Sephardic world through this investigation of my father.

My father is an example of the Sephardic world that is disappearing, forever, for lack of being told. Many writers have portrayed the Ashkenazi world, but sadly few have written about the Sephardic world in order to preserve it in a case, or perhaps to keep it alive and enduring, by showing the beauty of its values.

I had this project in my novel Sépharade, and I’d like to pursue this essential and existential path.

I’d like to go to Morocco, to Casablanca in the old synagogue street, to Marrakech and Essaouira in the footsteps of my family and the Jews of these towns, and to the Atlas mountains where Jewish scouts camped and helped poor families in the villages.

I’d also like to go to Canada to meet my father’s best friend, a member of Montreal’s Sephardic community, who could open his archives to me, and more broadly to meet some people who might be able to tell me something about Jewish life in Morocco and Montreal.

Meeting my family in Israel would enable me to investigate Sephardic Jews past and present, from north to south, where my grandmother lived in Beer-Sheva. It would also be necessary to interview all the students my father had, in Brussels, Switzerland, Lyon and Bordeaux, in the various communities where he taught and also at the university where he taught a course in general and comparative philosophy.

That’s why I’m submitting this application, to subsist through the time it will take to write this book – which I think is important for Jewish culture. With the sharp fall in the number of readers over the last four years, and the closure of bookshops with Covid, it’s becoming urgent to save writing, especially of specific, religiously-themed works. Indeed, I’d like to be able to continue this ambitious work and see it through to the end, so that it remains and is distributed around the world like some of my books in the past. This world of Jewish thought is close to my heart, and in my opinion, through its values of openness to tradition, generosity and transmission, it has much to contribute to our times.